The importance of tooling can not be overstated. There are no tools out there for the kind of deeply procedural game we're working on, and good tooling comprises 90% of what makes the game, as nearly all of our content is procedural in one way or another, and not handmade. If there's currently a lack of procedural content out there, it's precisely because of the lack of tooling.

So I set out to construct an IDE in which assembling procedures in a maintainable way became easier. Inspired by UE4's Blueprints, I began with graph based editing as a guide, as graphs make it relatively easy to describe procedural flow. As a warm-up, I wrote two tiny C libraries: a theming library based on Blender's UI style, and a low level semi-immediate UI library that covers the task of layouting and processing widget trees.

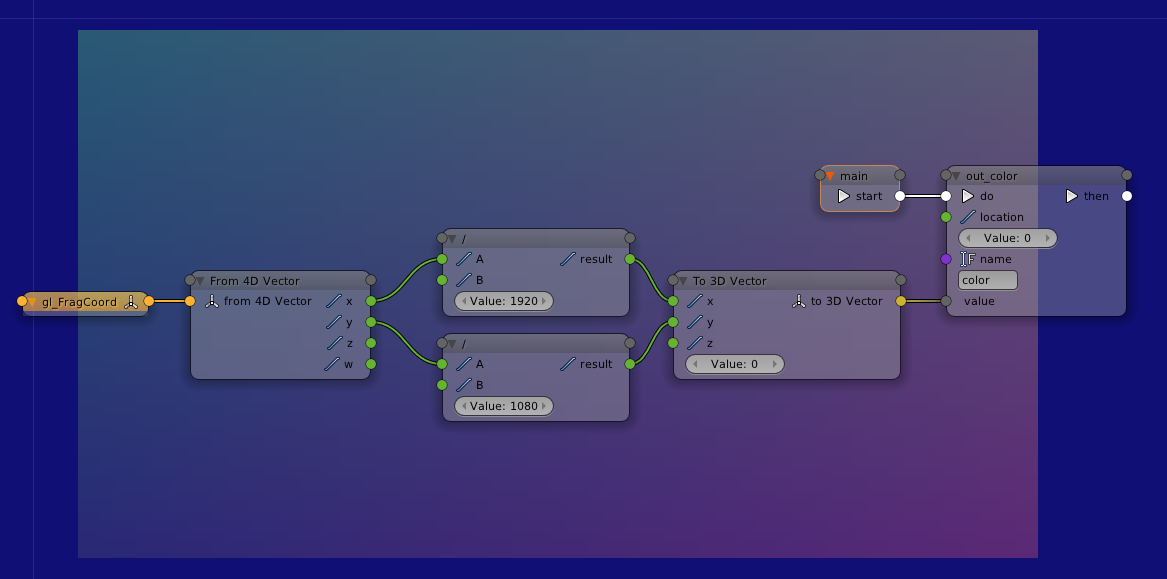

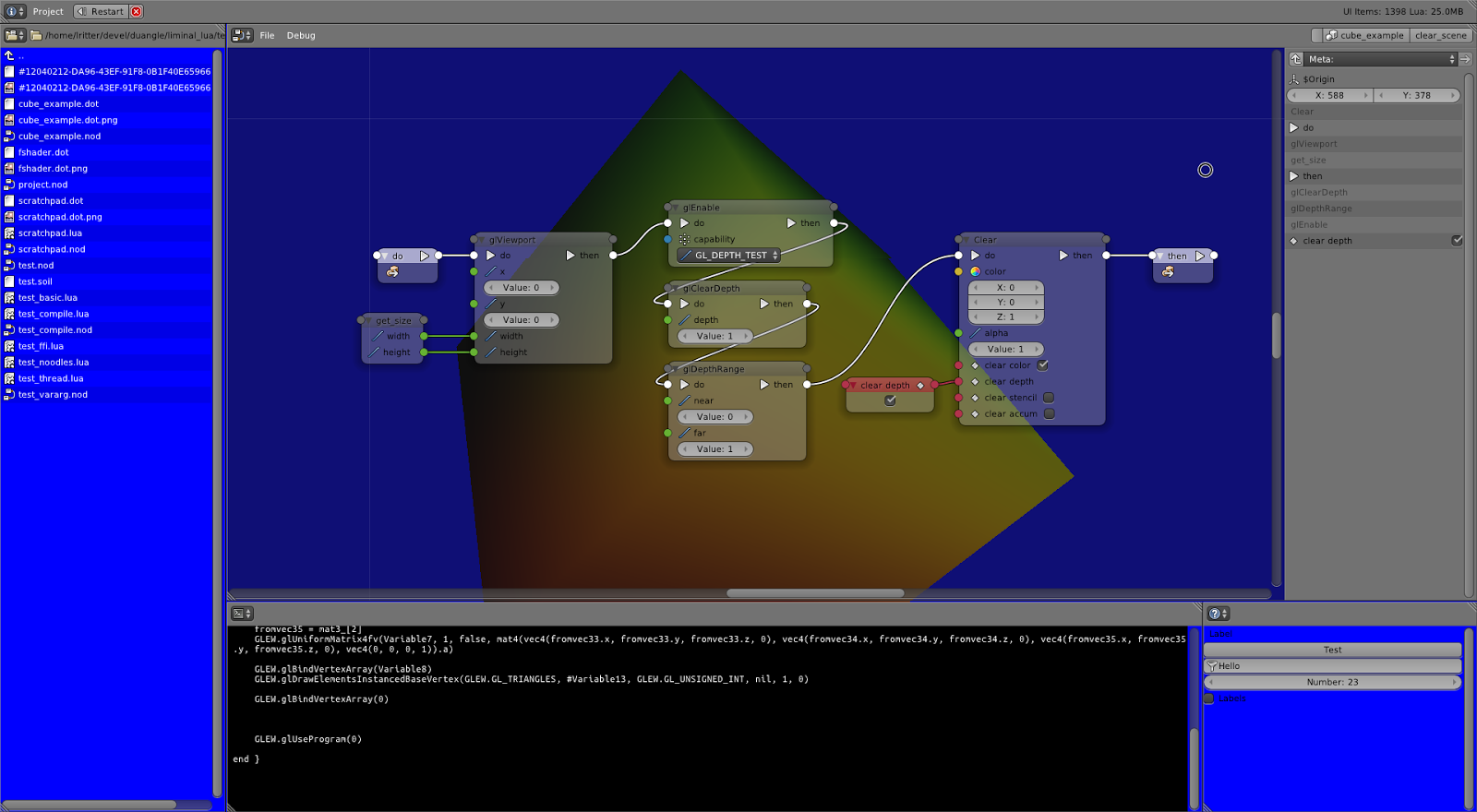

The IDE, dubbed Noodles, was written on top of the fabled 500k big LuaJIT. The result looked like this:

|

| Demonstrating compaction of node selections into subnodes, ad absurdum ;-) |

|

| A simple GLSL shader in nodes, with output visible in the background. |

|

| Noodles, shortly before I simplified the concept. Live-editing the OpenGL code for a cube rotating in the background. |

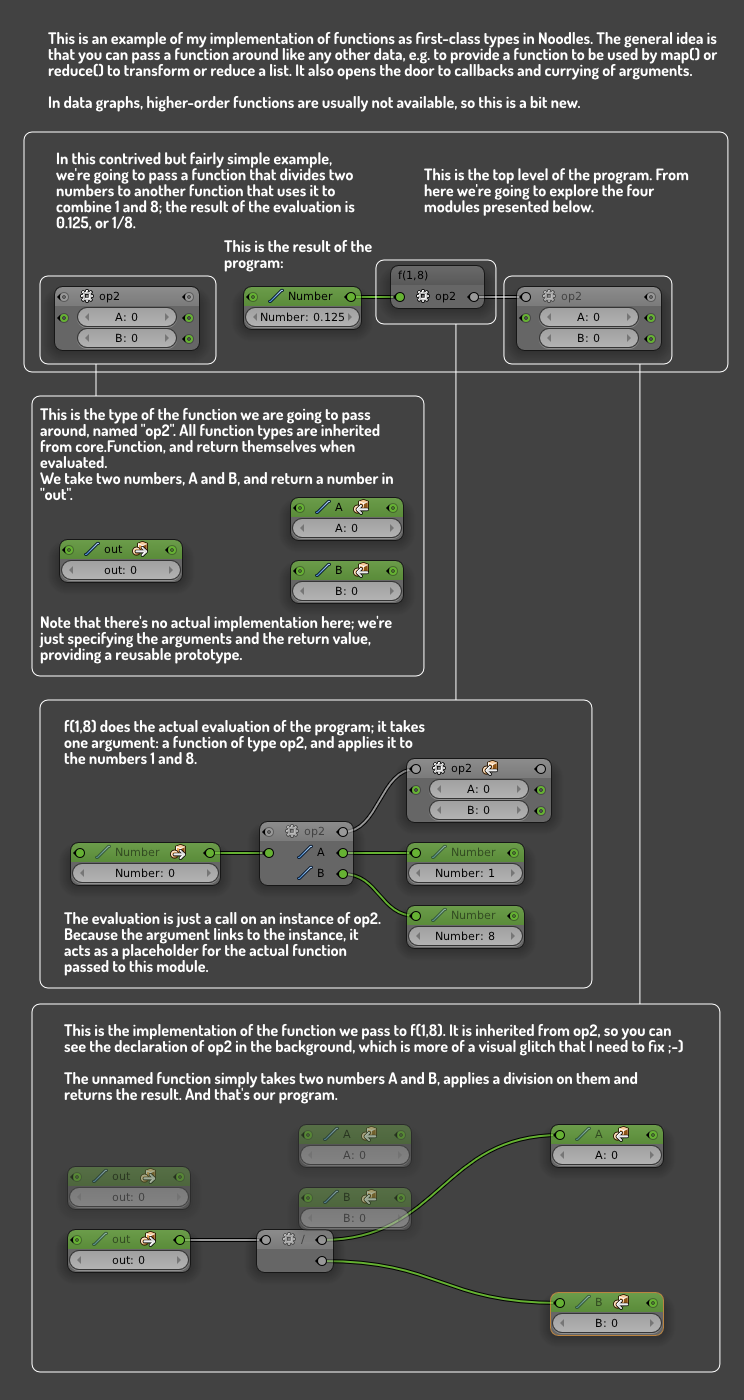

At this point, I didn't know much about building languages and compilers. I researched what kind of existing programming languages were structurally compatible with noodles, and data flow programming in general. They should be completely data flow oriented, therefore of a functional nature. The AST must be simple enough to make runtime analysis and generation of code possible. The system must work without a graphical representation, and be ubiquitous enough to retarget it for many different domain specific graphs.

It turned out the answer had been there all along. Since 1958, to be exact.

Did you know the first application of Lisp was AI programming? A language that consists almost exclusively out of procedures instead of data structures. I had the intuitive feeling that I had found exactly the right level of abstraction for the kind of problems we are and will be dealing with in our game.

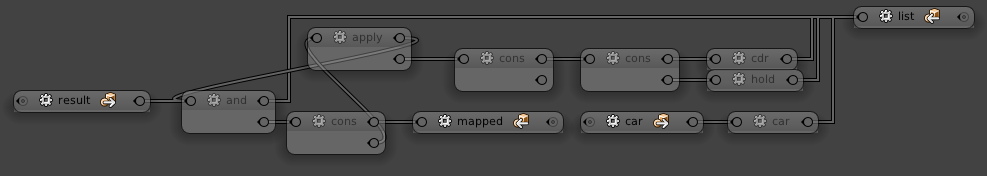

My first step was changing the computational model to a simple tree-based processing of nodes. Here's the flow graph for a fold/reduce function:

|

| Disassemble a list, route out processing to another function, then reassemble the list |

|

| Click for a bigger picture |

It became clear that the graph could be compacted where relationships were trivial (that is: tree-like), in the way Scheme Bricks does it:

|

| Not beautiful, but an interesting way to compact the tree |

|

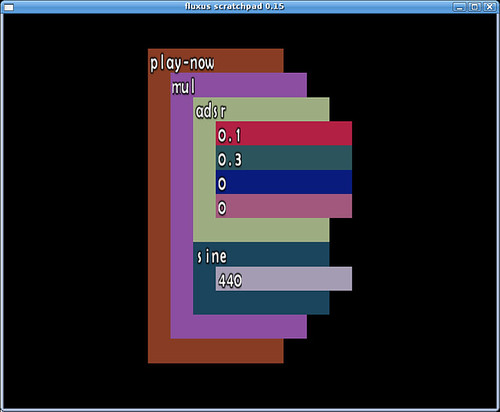

| A very early screenshot. Atoms are rendered as widgets, lists are turned into layout containers with varying orientation. |

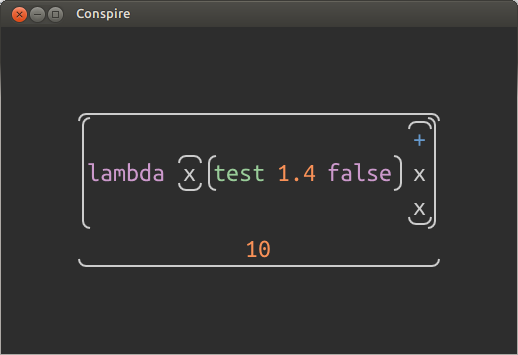

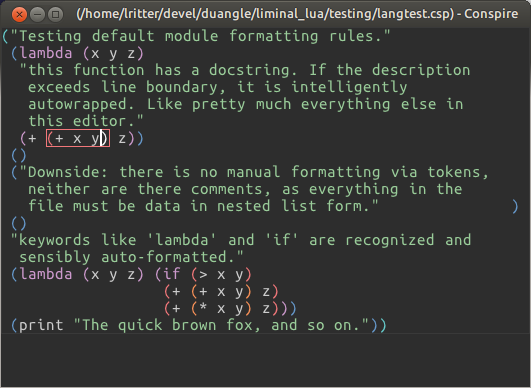

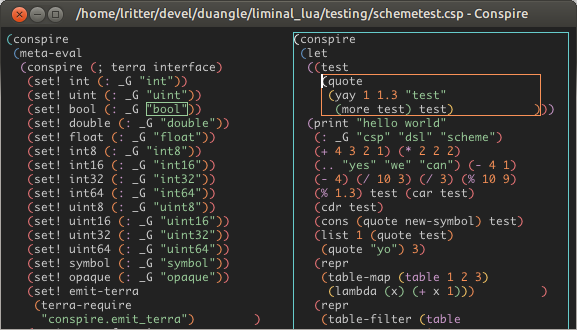

By default, Conspire maps editing to a typical text editing workflow with an undo/redo stack and all the familiar shortcuts, but the data only exists as text when saved to disk. The model is an AST tree; the view is one of a text editor.

|

| Rainbow parentheses make editing and reading nested structures easier. |

|

| A numerical expression is rendered as a dragable slider that alters the wrapped number. |

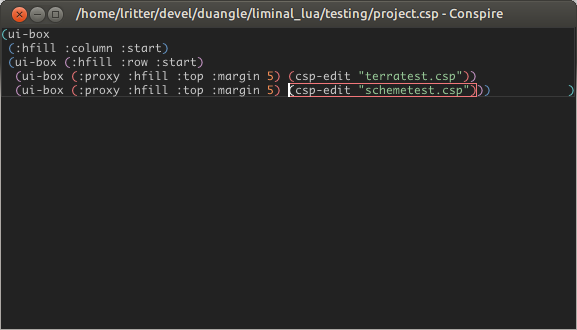

Using this principle, the editor can be gradually expanded with more editing features. One of the first things that I added was the ability to nest editors within each other. The editor's root document then acts as the first and fundamental view, bootstrapping all other contexts into place:

|

| The root document with unstyled markup. csp-edit declares a new nested editor. |

|

| Tab and Shift+Tab switch between documents. |

The idea here is that language and editor become a harmoniously inter-operating unit. I'm comparing Conspire to a headless web browser where HTML, CSS, Javascript have all been replaced with their S-Expression-based equivalents, so all syntax trees are compatible to each other.

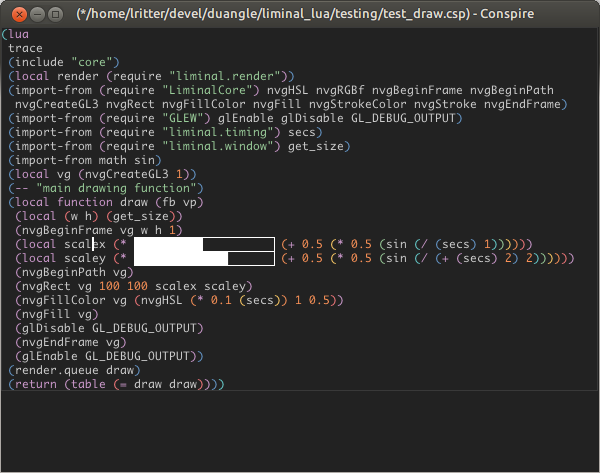

I've recently integrated the Terra low-level extensions for Lua and am now working on a way to seamlessly mix interpreted code with LLVM compiled instructions so the graphics pipeline can completely run through Conspire, be scripted even while it is running and yet keep a C-like performance level. Without the wonders of Scheme, all these ideas would have been unthinkable for the timeframe we're covering.

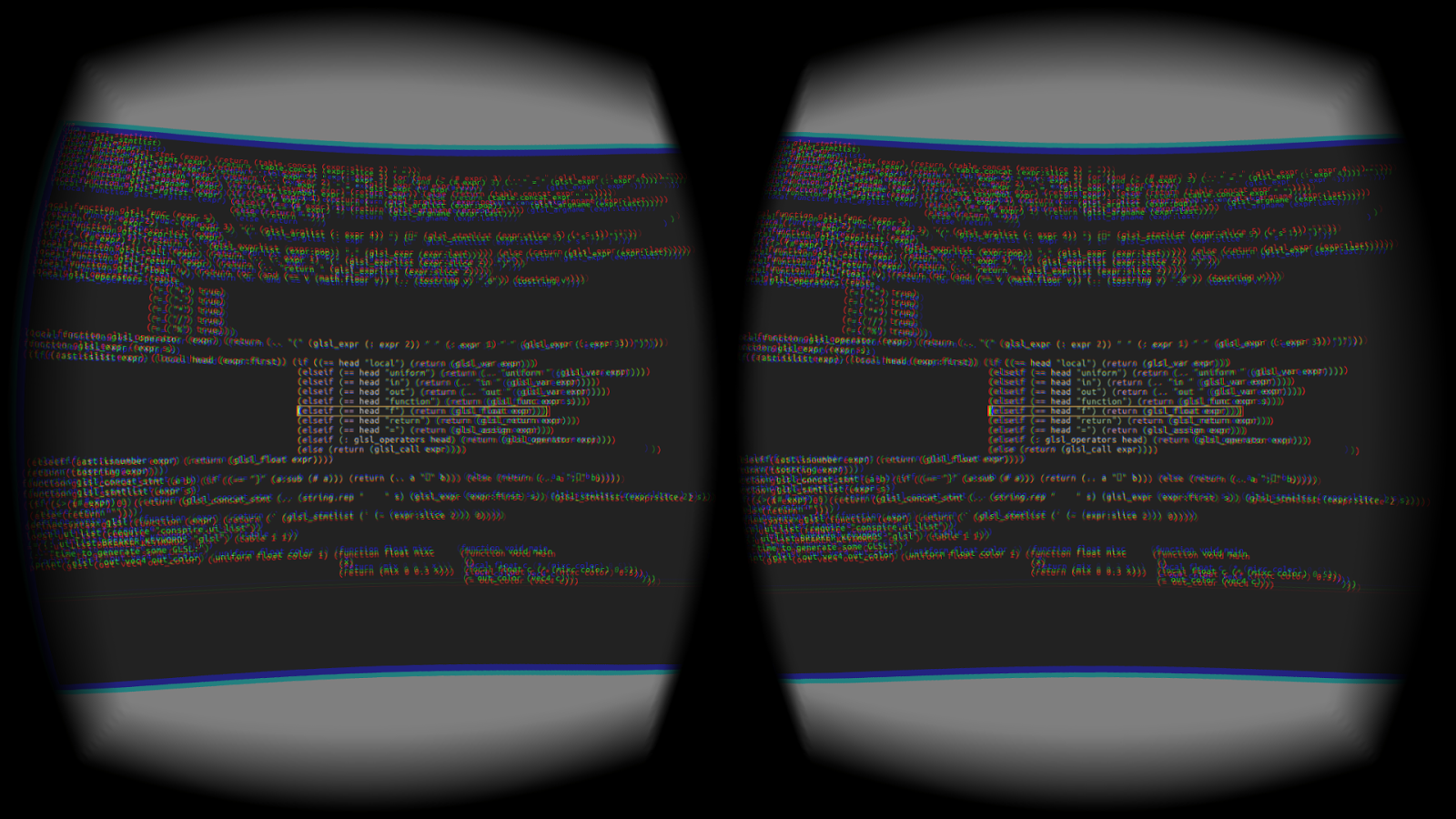

Oh, and there's of course one more advantage of writing your editor from scratch: it runs in a virtual reality environment out of the box.

|

| Conspire running on a virtual hemispheric screen on the Oculus Rift DK2 |